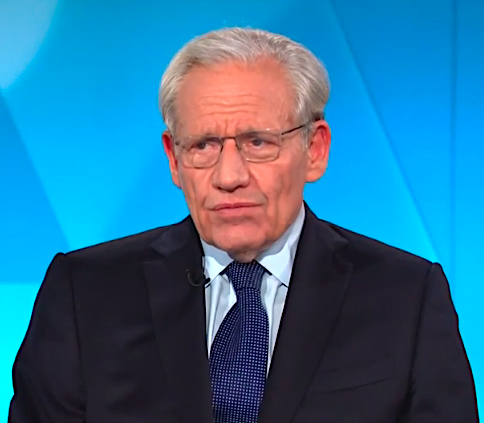

"I think journalism gets measured by the quality of information it presents, not the drama or the pyrotechnics associated with us.”

—Bob Woodward, investigative journalist who along with Carl Bernstein uncovered the Watergate scandal

Essential Question

How did journalists provide the public with news about Watergate and congressional hearings on President Richard Nixon?

Overview

Richard M. Nixon was a sitting US president seeking reelection when, on June 17, 1972, in what seemed at the time to be a minor, unrelated incident, burglars broke into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, DC. As it turned out, this was no ordinary break-in.

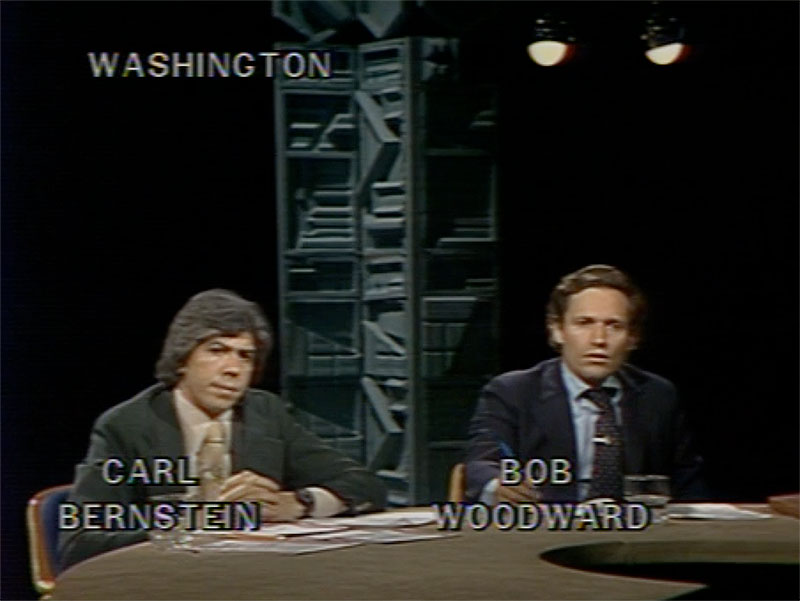

Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward would investigate the matter over the next few years. What began as a connection to the White House—the burglars were part of Nixon’s Committee to Re-elect the President—would evolve into a web of connections, illegal activities, and subterfuge by the president.

In this case study, you will:

- Analyze primary sources about the Watergate affair, including the role of investigative journalism.

- Provide analysis of Congress’s hearings into President Nixon and Watergate.

- Research and write your own front-page story on a modern-day example of investigative journalism.

Context

After journalists reported a series of stories connecting payments for the Watergate burglary to Nixon’s Committee to Re-elect the President, a special prosecutor was appointed. The prosecutor obtained a subpoena that required Nixon to deliver audio recordings of meetings he had with various assistants to the district court. Nixon refused to turn over all the tapes and transcripts, claiming executive privilege within the Executive Branch and that the court had no jurisdiction.

The dispute went all the way up to the United States Supreme Court in the case US v. Nixon. On July 24, 1974, the court unanimously ruled that the case should go before the courts and that the president’s claim of executive privilege was not absolute. He had to turn over all the tapes and transcripts.

On August 5, 1974, after complying with a Supreme Court order, the White House released secret tapes that revealed Nixon’s complicity in the Watergate cover up. It was a “smoking gun” of sorts, associating Nixon with the crime of obstructing the investigation. After pressure from Republican Senators who vowed to vote for his impeachment, Nixon resigned from office on August 8, 1974.

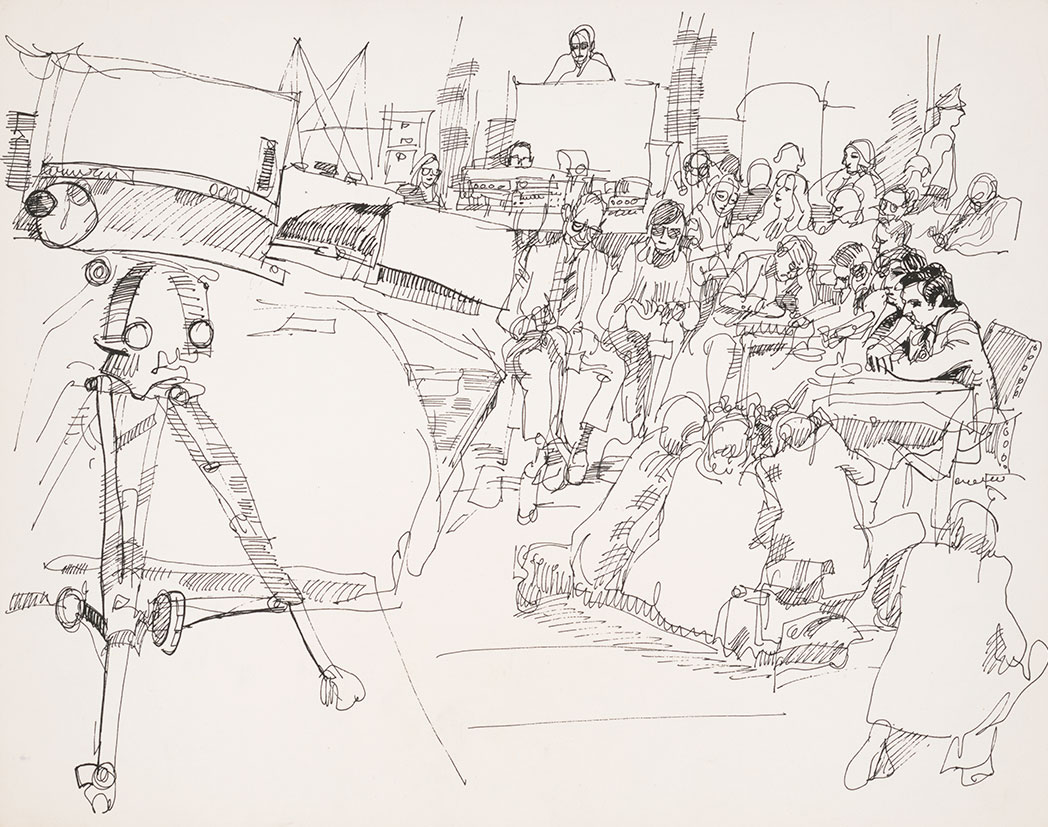

As Watergate played out, the American people read about the scandal in the newspapers and watched the situation unfold on their living room televisions. For the first time in the history of the news media, public television brought the scandal to life with live gavel-to-gavel coverage of the Senate hearings by coanchors Jim Lehrer and Robert MacNeil.

Discuss the following questions:

- What was the connection between the break-in at the Democratic headquarters at the Watergate complex and President Nixon’s reelection?

- Why is the Supreme Court’s ruling in US v. Nixon important as it pertains to how much power the president has?

- Do you think it was important that American people know the whole truth about the Watergate investigations? Why or why not?

Journalists

Many journalists covered the initial burglary at the Watergate complex, but Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post continued their reporting long after most reporters had moved on to other stories. The young men had the support of their hard-nosed executive editor, Ben Bradlee, and the paper’s publisher, Katharine Graham.

![Woodward's notes from the arraignment of the Watergate burglars. June 17, 1972. Notes read: “5 men arrested [Dept. chair] at Dem Nat headquarters. 2nd dist. w/ soph. photo equip. Stan Greg 229-1408 or 333-0133.”](/sites/default/files/media/watergate-introduction-journalists-2.jpg )

Woodward, born in Illinois in 1943, attended college at Yale and served in the navy for five years before embarking on his journalism career. His first job was at the Montgomery County Sentinel in Maryland, working there for a year before going to work at the Washington Post in 1971.

Bernstein was born in Washington, DC, in 1944, and began his reporting career at the age of sixteen at the Washington Star. However, the paper unofficially required a college degree to write articles, so Bernstein, who had not finished college, left to work for the Elizabeth Daily Journal in New Jersey. At the age of twenty-one, he won a statewide award for investigative reporting. Bernstein got a job at the Washington Post in 1966 and in 1972 was assigned to cover the break-in at the Watergate complex with Woodward. Both men rose to national fame with their steadfast investigative journalism of the Watergate scandal.

Woodward and Bernstein published All the President’s Men in June 1974. The book chronicled the Watergate scandal from the beginning through the revelation of the White House tapes. They would later write a second Watergate book titled The Final Days, continuing the story of the Watergate scandal from All the President’s Men through Nixon’s resignation.

The Washington Post was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for its Watergate reporting. Woodward continued his career as an investigative journalist with the Post and is currently an associate editor for the paper. He has written over twenty books, is the recipient of numerous journalism awards, and was instrumental a second time for the Washington Post winning a Pulitzer Prize, this time for its coverage of 9/11 in 2002. Bernstein moved into TV broadcast journalism but has also authored numerous books.

Many other journalists rose to prominence during Watergate in both print and broadcast media. In May 1973, US Senate hearings began probing into the Watergate scandal. The hearings were broadcast live on commercial television and replayed on public television during prime time, when many people were at home. Every evening, the news anchor team of Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer set up the day’s hearings with brief commentary then let the hearings play out. The anchors only interrupted at natural breaks for station identification.

At the end of the hearings MacNeil and Lehrer provided ten minutes of commentary. In an effort to involve viewers, MacNeil asked viewers what they thought about the hearings and asked them to write their thoughts down and send them to the anchors. Though not as instantaneous as Twitter or Facebook, by the sixth day of hearings the program had received over seventy thousand letters, nearly all of them favorable toward the broadcast.

In the early 1970s, most reporters were white men and the news media was still known for its “old boys’ club” mentality. There were some notable exceptions. Helen Thomas, who you will be learning about in this case study, became the first female White House correspondent for United Press International (UPI) wire service and the first female officer at the National Press Club. She covered ten presidents over the course of her career. Television reporters Barbara Walters, Leslie Stahl, and Connie Chung also covered Watergate.

Discuss the following questions:

- What was the educational and work experience of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein before being assigned to cover the break-in at the Watergate complex?

- Describe how Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer of public television hosted the coverage of the Watergate hearings. Why do you think this style of journalism was so popular with viewers?

- Helen Thomas was known for asking the “uncomfortable questions” during press briefings. Do you think members of the press should confront public officials, including the president, with questions that hold them accountable for their statements and actions? Why or why not?

News Format

In May 1973, the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities began televised hearings investigating the Nixon administration’s ties to the Watergate scandal. In addition to coverage by newspapers and the three major networks (ABC, NBC, and CBS), public television joined the media landscape. The publicly funded program, National Public Affairs Center for Television (NPACT), which eventually became PBS, gained attention for airing live coverage of the Watergate hearings and rebroadcasting them at night.

Television coverage of the hearings was different than today. There was no theme music, no pundits offering their opinions, and no social media weighing in, only calm news anchors narrating the events and explaining the issues. This coverage allowed viewers to draw their own conclusions as to what happened and whether President Nixon had done anything wrong.

Discuss the following questions:

- How did television provide the American public with broad coverage of the Watergate scandal? Do you think the press in general and television news in particular should report on investigations into government wrongdoing? Why or why not?

- How does television coverage of the Watergate scandal compare to the way cable news programs cover government scandals today? Which style do you think better serves the public?