”Energy rightly applied and directed will accomplish anything.“

—Nellie Bly, investigative reporter

Essential Question

How does investigative journalism bring awareness to problems and help support reform efforts?

Overview

In this case study, you will analyze primary sources on the mental health reform movement of the mid-nineteenth century, which was spearheaded by Dorothea Dix. Hospitals were overcrowded, provided little training for nurses, and lacked translators for many of the poor immigrants who were wrongly committed in the first place. Medical knowledge of how to care for those with mental health issues still had far to go.

In addition, you will examine primary sources about the young journalist Nellie Bly who was given the assignment to go undercover as a patient inside the notorious New York City Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island in New York.

The term “lunatic asylum” was used in the 1800s but dropped out of the medical lexicon by the end of the century and is seen as a derogatory term today.

To complete her assignment, Bly feigned mental illness at a women’s boardinghouse and was soon committed to Blackwell’s. Within days of her release, Bly published her exposé in the newspaper the New York World. In it, she described the hospital’s inhumane living conditions and the staff’s cruel treatment of their patients. Her work led to government reforms and was an early example of a new type of reporting called investigative journalism.

NEW: A supplementary vocabulary guide (Google doc) is now available for this case study. PDF version here.

Context

Throughout the 1700s in colonial America, the treatment of people with mental illness was almost always barbaric. Many mentally ill individuals were placed in prisons—often chained to the walls—and lacked appropriate clothing for the season. While some families took responsibility for their mentally ill relatives, many more would hide them in attics or sheds in order to avoid embarrassment. In the 1770s, facilities began to be built for the mentally ill but still were not designed to help patients get better, since most mentally ill people were seen as incurable.

The 1800s ushered in reforms in mental health, including the construction of asylums, as patients were no longer seen as having moral failings but rather treatable medical conditions. These reforms coincided with other humanitarian efforts focused on temperance (efforts to ban or discourage the use of alcohol), women’s rights, prison reform, and the abolition of slavery.

New Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, building, Pa. Stereograph showing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane under construction, with many workers posing in foreground. ca. 1859. Library of Congress

Fenced-in walkways of the Richardson Olmsted Complex, the 1870 Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane, Buffalo, New York. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, 2018. Library of Congress

In the 1840s, Dorothea Dix led the reform movement for mental health and advocated for the “moral treatment” of individuals, for example that patients should no longer be kept in shackles or straitjackets. Dix successfully lobbied state legislatures and Congress for the construction of public hospitals for the mentally ill.

As is typical at many large institutions, problems began to develop inside the hospitals that arose. Dix blamed much of the problem on poor administrative leadership and a lack of funding, which led to overcrowding and poor care. Newspaper reports exposed the inhumane conditions inside these hospitals, taken from accounts by former patients or family members. However, most journalists were forbidden to see what was actually going on inside for themselves.

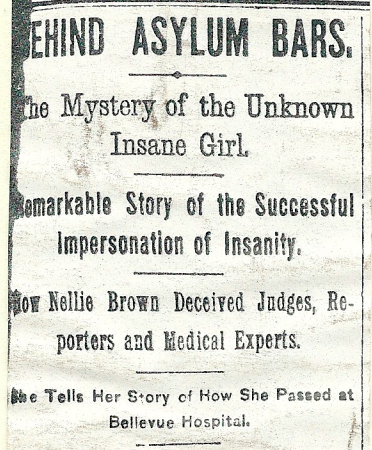

“Behind Asylum Bars” by Nellie Bly. The New York World. Oct. 17, 1887. Permission has been granted for educational purposes only courtesy of NYU Digital Library Services.

One notable exception was twenty-four-year-old Nellie Bly. In 1887, Bly was able to get herself committed to the asylum on Blackwell’s Island, an overcrowded, state-run mental institution. Shortly upon her release, she wrote a groundbreaking piece for the newspaper the New York World about her experience. Bly’s exposé won her instant notoriety and helped to bring widespread attention to the problem.

Discuss the following questions:

- How was mental health treated in the 1800s compared to the 1700s?

- What contribution did Dorothea Dix make on advancing mental health treatment? Why were her accomplishments important?

- Describe the unusual way Nellie Bly found out what life was like in an asylum. Do you feel this was an ethical way to get a story? Why or why not?

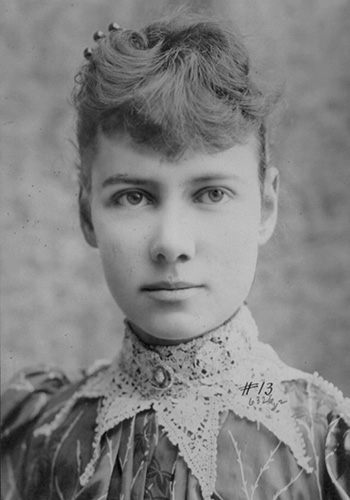

Nellie Bly, 1890. Library of Congress

Journalists

The newspaper business was very competitive in the late nineteenth century, especially in big cities. Publishers and editors sought out sensational stories of poor urban conditions to increase circulation. If reform and improvement came about in the process, so much the better. One reporter sought more than the sensational and was one of the first to develop a form of reporting known as investigative journalism.

Elizabeth Jane Cochran, a.k.a. Nellie Bly, was one of fourteen siblings growing up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Early in life, she was compelled to speak truth to power when she testified on her mother’s behalf against an abusive stepfather. Later, she studied to become a teacher, one of the few professions open to women at the time, but dropped out due to lack of funds.

At age twenty, Bly read a newspaper column in the Pittsburgh Dispatch entitled “What Girls Are Good For” that argued womens’ value was only in birthing children and keeping house. Incensed, Elizabeth wrote a letter in response, pointing out the article’s negative representation of women. The managing editor of the Dispatch was so impressed that he printed her rebuttal letter and offered her a full-time job.

After a series of Bly’s investigative articles on female sweatshop workers received several complaints from factory owners, she was reassigned to the Society pages. Bly soon became dissatisfied with her new assignment and traveled to New York City, where she got a job writing for the New York World.

In one of her first assignments, Bly had herself committed to the New York City Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. There she experienced the filthy conditions and abusive treatment firsthand. She interviewed patients who were committed after only a brief examination. Many of these people were immigrants who didn’t speak English.

In 1887, the New York World published a series of articles that were later compiled into a book, Ten Days in a Mad-House. The articles caused a major sensation, prompting city officials to implement reforms and bringing Bly lasting fame.

Not long after Bly’s exposé, a group of journalists who came to be known as muckrakers began reporting on issues of social injustice in an in-depth way that connected to the public on an emotional level. (Be sure to check out the case study on the Muckrakers to learn more.)

Discuss the following questions:

- Why do you think circulation increased when nineteenth-century newspapers printed sensational stories about poor urban conditions?

- What does the story about how Nellie Bly got the job at the Pittsburgh Dispatch tell you about her personality and ambition?

- What does Bly’s reporting from the “Mad-House” tell you about society’s attitudes toward mental health and ethnic prejudice at the time?

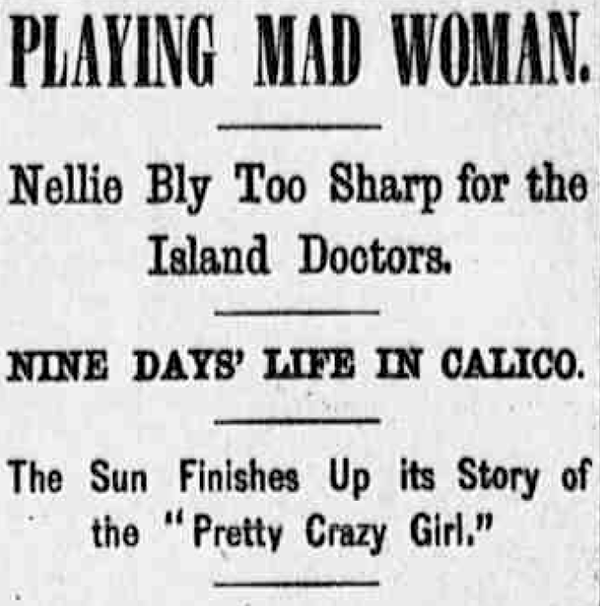

Newspapers like the Sun wrote their own stories about the “mad woman” known as Nellie Brown whose identity remained a mystery to authorities. The Sun’s editors were not pleased to learn that the woman was in fact a reporter for their rival paper. Oct. 14, 1887. Library of Congress

News Format

During the late nineteenth century, the newspaper business became not only “big business” but highly competitive and sensational as publishers battled for increased circulation to grow their advertising revenue. Some newspapers printed yellow journalism, exaggerated stories with sensational headlines. Bly worked for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, which became one of the most famous examples of yellow journalism but also published hard-hitting, investigative articles.

Newspapers like the World also engaged in “stunt journalism”—or “immersive journalism”—in which reporters like Bly embedded themselves into the subject of their story. The result is a deep look into the inner workings of business and government. The stories often revealed the dangerous living and working conditions in tenement housing and factories. The writing was vividly descriptive and condemning, but oftentimes told only one side of the story. Stunt journalists were sometimes criticized when their experience affected them so much that their stories lost objectivity.

Discuss the following questions:

- What is meant by “investigative journalism”? What are some examples of this today?

- Why was “investigative journalism” sometimes called “stunt journalism”?

- What was some of the criticism of investigative journalism at this time?